Parker-Fersen Residence

The Parker-Fersen residence, one of Seattle’s great historic houses, has been fortunate to have owners who care greatly for its preservation and continued life as a family home. It has been our privilege to work with the current owners of this house, a City of Seattle Landmark, on exterior maintenance and restoration, a complete remodeling of the kitchen, and other updates. Where exterior work adhered to national standards for preservation and restoration, remodeling of the kitchen was more interpretive, creating a “cook’s kitchen” and family space that combines period details with modern conveniences.

While the Parker-Fersen residence had been well maintained, age and the elements dictated a more serious exterior restoration effort including complete replacement of the roof. We were fortunate to work with a team of fine craftsmen to complete this work over a period of several years, returning the home to a pristine state it had not seen for some time.

Since the house is a City of Seattle Landmark, restoration was guided by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for preserving, rehabilitating, restoring and reconstructing historic buildings. And all work to designated portions of the house was reviewed and approved by the Seattle Landmarks Board, which is entrusted with overseeing our city’s built heritage.

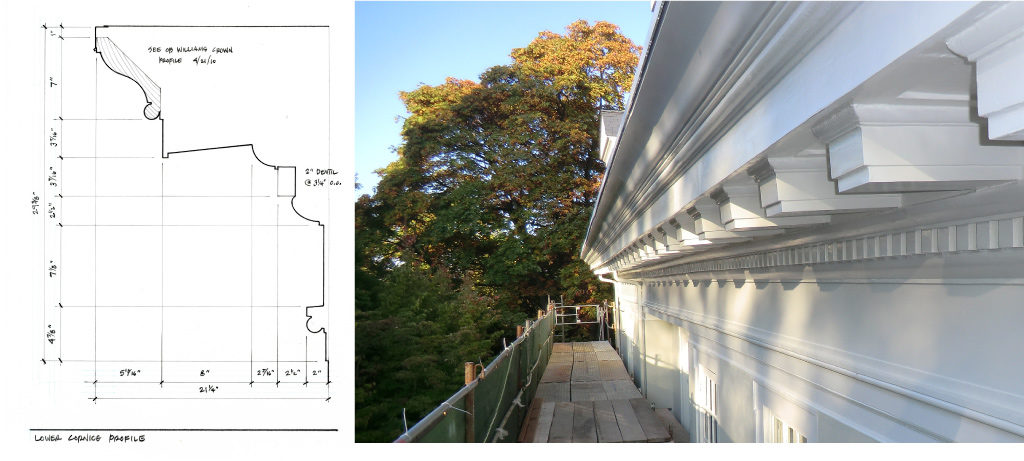

As we began to inspect the house from the ground, ladders, and scaffolding, we found many areas where the cornice was sagging, rotten, or both. Careful measured drawings of the existing profile were prepared so that new, matching trim could be milled by Seattle’s O.B. Williams.

Above the cornice were built-in gutters that, like the extensive areas of flat roof, presented interesting challenges; not only had the roof and gutters leaked, sagging often meant water no longer flowed to the drains. Under the skilled eyes of Gary Hill and Peter Eskildsen, rotten trim was replaced, gutters were rebuilt—and redirected to drains—and appropriate flashings were installed. Flat roof areas were covered with KEE membrane and the sloped roof was covered with Ecostar Majestic Slate, both chosen for their long life and environmental friendliness.

In several areas special detailing was called for. On the west side of the house were columns rise two stories from the porch roof, the original column bases were founded coated with asphalt and badly deteriorated from a century of weather. After stabilization of the wood with epoxies, the membrane was turned up and flashed, here seen during construction and in a detail by Marvin Anderson Architects.

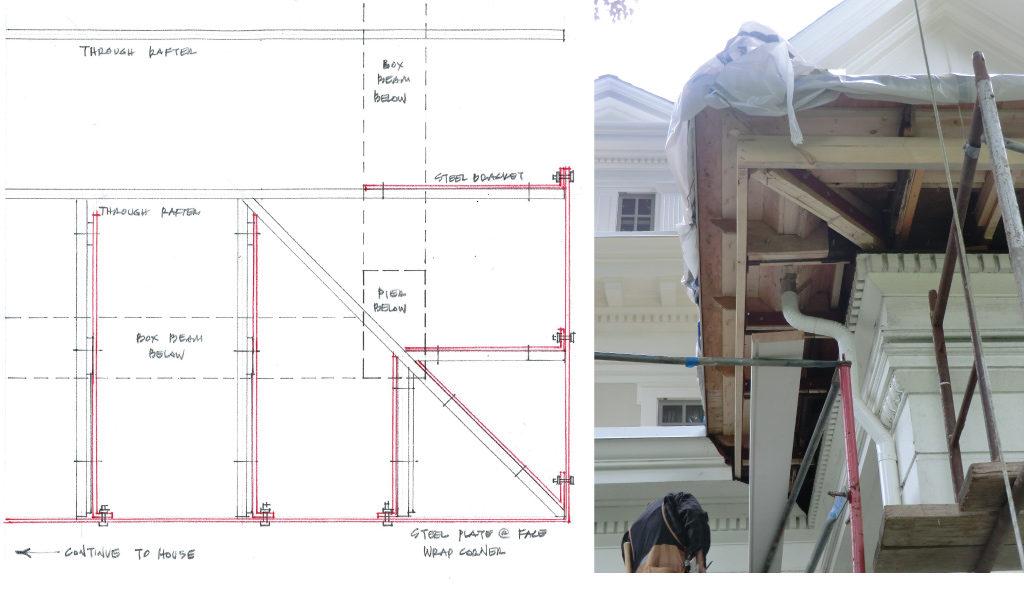

At the Porte Cochere, age, gravity, and poor previous remodeling efforts had all resulted in a badly sagging cornice. Marvin Anderson worked closely with Steve Lidicker at DCI Engineers to devise a method of steel reinforcement that would work with existing framing and be invisible once finishes were re-installed.

In these pictures work at the Porte Cochere is complete. The roof has been replaced, the sagging cornice is now level, the soffits are vented with punched aluminum grilles in the Grecian pattern, appropriate to the style of the house, and the trim gleams in a new coat of paint. As with all successful restorations, one cannot distinguish the new work from the old.

Restoration is hard work and if done well, is invisible when complete. While challenging, it is also extremely rewarding, for in a culture that often privileges the new it preserves our built heritage for future generations.

When the Parker house was built, the kitchen area consisted of three spaces, all used solely by staff. Just inside the back door was a pantry where food and goods were delivered and stored, followed by a cooking kitchen and, next to the dining room, a serving pantry. Despite multiple remodels over the past century, a few original details remained—cabinets and a fragment of floor tile—and were used as the basis of design for the new kitchen.

The remodeled kitchen combines the original three spaces into one large room with discrete areas for storage, prep, cooking, and clean up tasks. Also important was an island where friends and family could hang out. Cabinets are classic white and countertops black granite for durability. The dark stained wood trim is mostly original, and the lights (which were in the kitchen) date from the 1920s, now rewired to meet current codes. This photo looks toward the original back door into what was once the pantry.

Computer models were used throughout design to help visualize the combined space and study how the various details would fit together. This view looks toward the dining room door and new refrigerator, behind which is storage for dining room table leaves. Tucked discretely into the corner is a television, and on the left is the Aga range which anchors the kitchen and remained in the kitchen throughout the remodel.

A long narrow space, the new kitchen is encircled by a multi-colored, porcelain mosaic tile border. The pattern is original to the house and comes from a one-foot-square fragment of tile found in the basement. Since none of the other tiled rooms in the house had been remodeled, we believe this fragment was once part of the kitchen floor, removed in one of the past remodels. Except for one tile, which was changed slightly, the colors are also original to the house.

As the tile border unites the room into a whole, its pattern, rhythm, and corners were considered carefully. Highly detailed colored tile layout drawings were created to study various layout options and to guide construction. Tile was laid first, fitted carefully into a room that after demolition we found lacked parallel walls or square corners. Next came the cabinets, which were carefully placed so that their front edges landed on tile grout lines and their slightly tapered counter widths could not be seen. While consciously noticed by few, this attention to detail and careful craftsmanship are unconsciously sensed.

New cabinets were modeled on the few originals that remained and feature period details like sawtooth shelf brackets and inset glass upper cabinets doors with exposed latches and ball-top hinges. But we also incorporated modern features like modern plumbing and appliances, a built-in vacuum system, and undercabinet lighting. The leaded glass window between the cabinets is new, detailed to match a period window installed in the kitchen during a previous remodel, and below it are carefully concealed refrigerator drawers. Along the wall, shallow felt lined plate drawers were created to safely store fine china, critical in earthquake country.

Before designing the tile backsplash and range back we studied tile and millwork details throughout the house, selecting a classic small white “subway tile” with crackle glaze set in running bond, both for its period appropriateness and its ability to quietly unify the kitchen. Tile behind the range was laid in a basketweave pattern framed with an Ann Sacks beaded, egg-and-dart border that picks up on original details in the house. The Aga range, which had been in the house for many, many years, was moved just a few inches in the final design, capped by a new commercial grade stainless steel hood.

The owners, who are serious cooks and entertain often, are thrilled with their new kitchen, both for how well it functions and for how well it fits the character of this historic home.

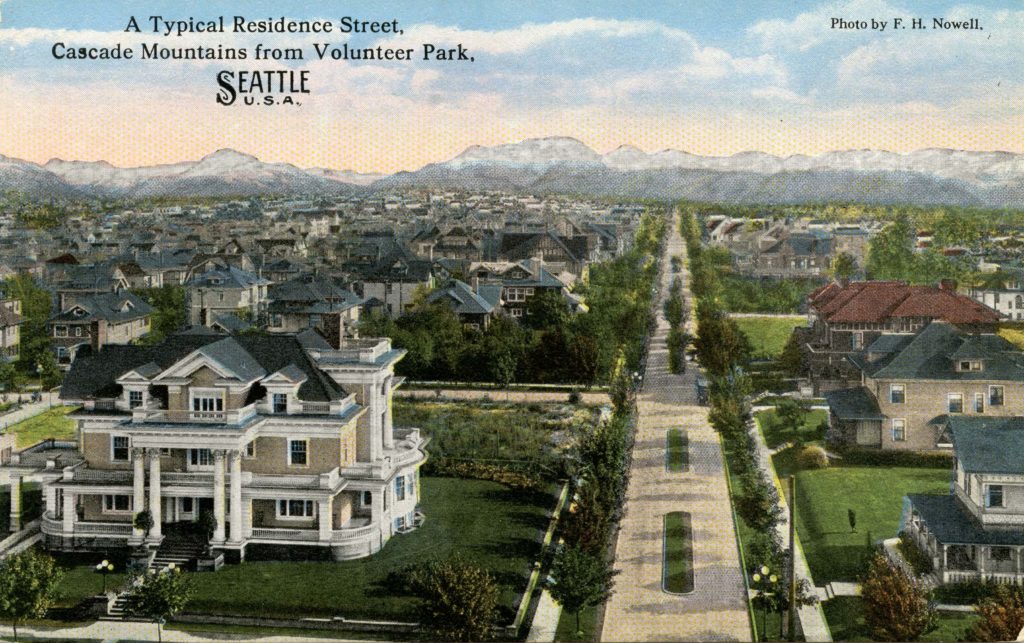

Postcard of Millionaire’s Row. Private Collection.

George Parker was not a wealthy man when he came to Seattle in the summer of 1906, but he was ambitious. Described as having a “suave manner and convincing speech,” he was a born salesman, and as West Coast representative for the United Wireless Telegraph Company, Parker was a tireless promoter of new technology — the promise of wireless communication not only among stations on land but with ships far out at sea. Within two years Parker’s fortune reached $1 million, a vast sum at the time, and with his wife Evvie he decided to erect a large home where the south end of Fourteenth Avenue, then dubbed “Millionaires’ Row,” met Capitol Hill’s Volunteer Park.

Parker family. Parker Family Collection.

The Parkers chose Frederick Sexton to be their architect. Not one of Seattle’s ‘name’ architects, Sexton was an odd choice, having built his career largely by designing commercial buildings and schools in Tacoma and Everett before a stint in South Africa searching for gold. When he returned to the United States in 1900, Sexton abandoned his wife and children in Everett to settle in Seattle, then growing rapidly as the jumping off point for Alaska’s Klondike gold rush. Over the next decade Sexton concentrated on residential architecture, designing apartment houses and single family homes in a variety of styles. For the Parkers he designed a sophisticated colonial revival home with a grand two-story front porch facing the park and elevated portico, also with two story Corinthian columns, facing Millionaires’ Row. The interiors were by George Davis and Oliver Halbert, a decorating team responsible for furnishing many fine houses in the city, and feature stained glass, tapestries, decorative tile, hand-painted murals, and extensive fine woodwork.

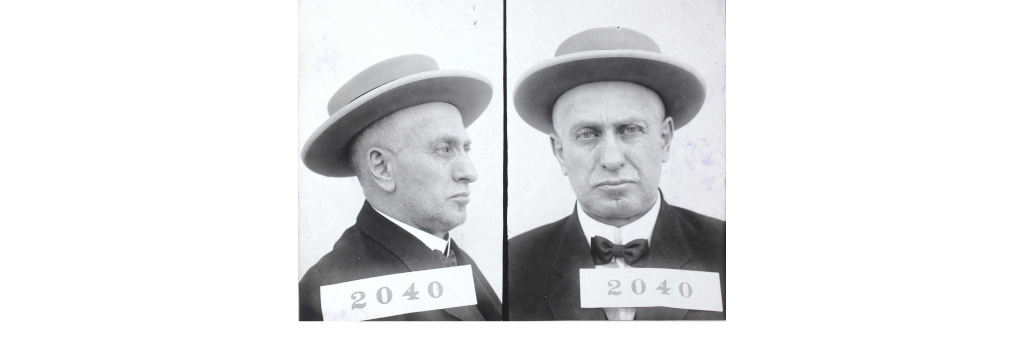

While Parker’s wealth was very real, United Wireless was but a mirage, a shell company built entirely on shares of worthless stock. On June 15, 1910, barely a year after the Parkers moved into their new home, officers of United Wireless were arrested for postal fraud by government agents. The company’s value was a fraction of what was claimed, its promised stock returns a Ponzi scheme. After a short trial in New York, George Parker was convicted and sent to the federal penitentiary at McNeil Island near Tacoma. Through numerous lawsuits over many years Parker forfeited much of his wealth, but having put title to much of their other real estate in Evvie’s name, the Parkers were able to retain the house on Capitol Hill, to which George returned when paroled in 1912.

George Parker, National Archives and Records Administration Pacific Alaska Region, Seattle, Washington; McNeil Island Penitentiary Prisoner Identification Photographs; ARC Number: 608846; Box Number: 2.

Once a salesman, always a salesman, George Parker then began a new career selling cars with his two sons Frank and Charles. They opened a showroom on Broadway and raised money to build an entirely new car designed by Charles Parker named Ajax at a factory in Ballard. For the next decade the Parker Motor Car Company prospered under George’s direction then quietly closed its doors after his death in late 1926; despite having sold shares in the new car company, Ajax never hit the streets.

The Parker house with a ‘For Sale’ sign in the late 1930s. Parker Family Collection.

In March 1939 Evvie Parker sold the house across from Volunteer Park to Baron Eugene Fersen, a Russian nobleman, author, teacher, and founder of the Lightbearers, a scientific philosophical organization. Fersen quickly tackled years of deferred maintenance and filled the Parker house with artwork and furnishings from his grand apartment in Paris, turning it into his home, a series of galleries, an educational center, and the official world headquarters for the Lightbearers. There for nearly 20 years Fersen wrote and lectured regularly as the organization grew worldwide. After Fersen’s death in 1956, Lightbearers College and Great Lightbearers Center remained in the home as Fersen’s Science of Being knowledge attracted new adherents. By the mid-1980s the house was again in need of serious maintenance, prompting the organization to search for a new buyer. In 1987 the house was designated a City of Seattle Landmark and sold to new owners who embarked on renovation and restoration. Fortunately for the house and for Seattle the house remains in the hands of owners who value its rich history.