Stratton Residence

The Stratton residence was simply tired when our clients purchased it: years of neglected maintenance had led to leaks in the roof, rotting trim, drafty windows, and barely functioning mechanical and electrical systems. Inside, a series of former remodels had resulted in spaces that were awkward in proportion and flow, and poorly suited to contemporary family life. Working in very close collaboration with our clients we embarked on a top-to-bottom remodel and restoration, saving many original spaces and details while completely reconfiguring the service spaces into an open family kitchen and family room. Bathrooms were largely gutted, systems were replaced, walls were insulated, and historic windows were weather-stripped and restored. On the exterior a covered porch was added to match the reclaimed original covered porch, creating symmetry about the new front entry porch and for the first time bringing order, balance, and proportion to this marvelous historic home.

Marvin was designer and project architect of the Stratton House while an employee of Sullivan Conard Architects.

In the summer 1902, Judge Julius Stratton and his wife Laura became one of Seattle’s first families to move from central Seattle to the new Denny-Blaine neighborhood on a knoll above the shore of Lake Washington. Like many who would follow, Stratton chose to leave the city’s bustle for one of its new suburban tracts made accessible by an expanding web of streetcar lines that could daily carry the Judge to his work downtown. Having previously worked with him on the design of a house on Madison Street, Stratton turned again to architect William Boone, now in practice with the young James Corner.

Puget Sound Regional Archives, 1937.

Born in Pennsylvania and self-taught in architectural design, Boone (1830-1921) worked many construction jobs in Chicago, Minneapolis, and San Francisco before arriving in Seattle around 1881 where he designed numerous prominent buildings including in 1898 a residence for pioneer Henry Yesler, which was then Seattle’s largest home occupying a full block on the edge of the city’s core. When the great fire hit Seattle in 1889, over half of the major buildings destroyed in the 30 block conflagration were of Boone’s design. By the time Boone took James Corner (1862-1919) as his partner in 1900 he was 70 years old and nearing the end of his career. Corner, on the other hand, was just over half his age, and had come to Seattle after apprenticeship in Boston where he had published two books on Colonial and Federal architecture.

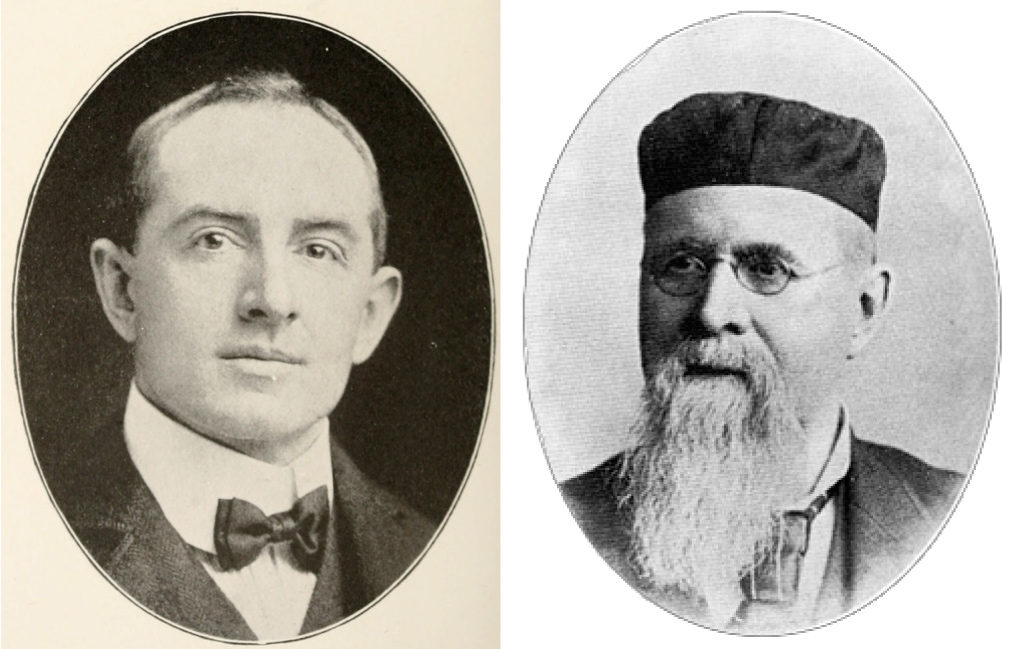

James Corner (left) & William Boone (right).

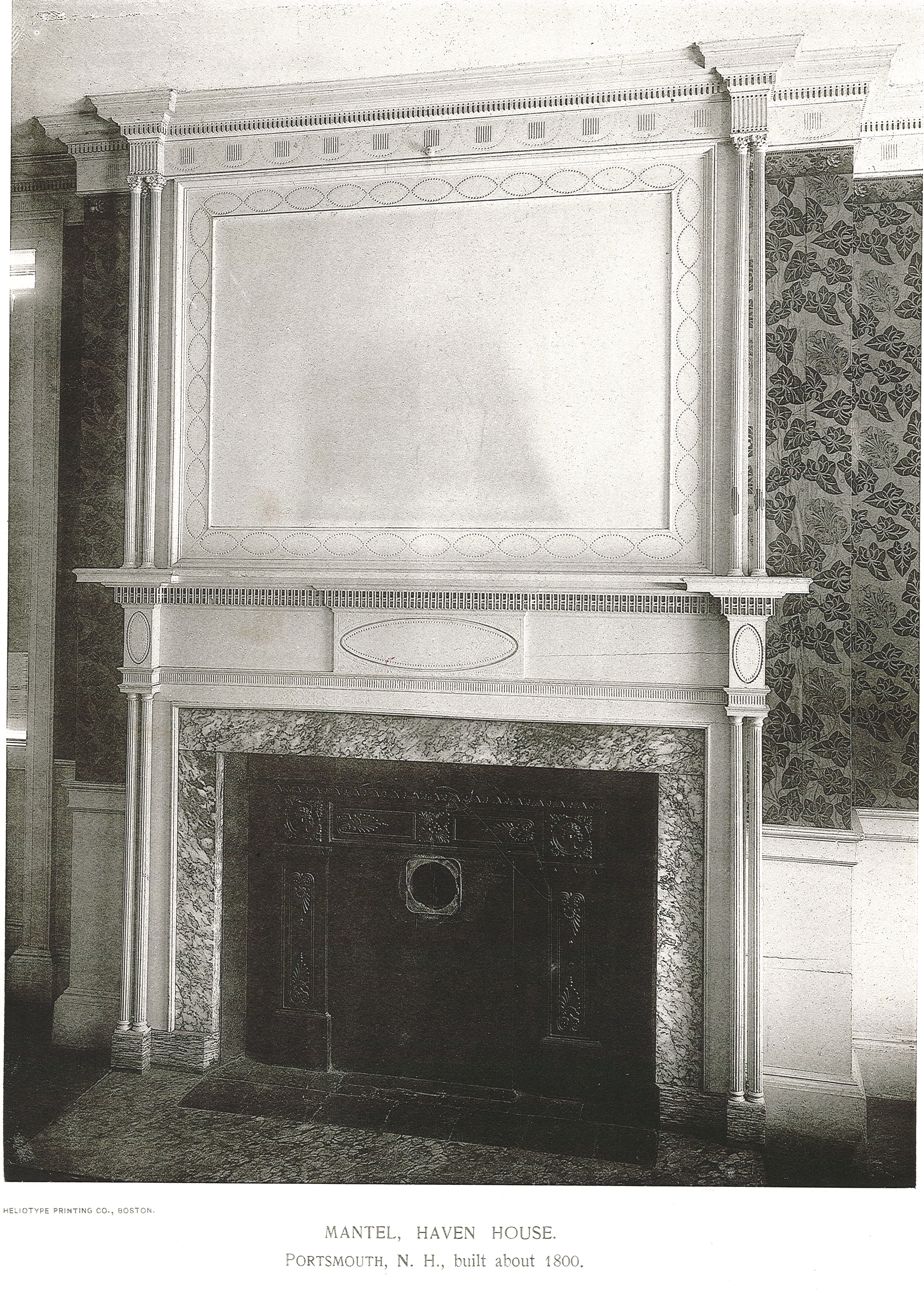

With its plain round porch columns, restrained ornament, banded shingle skin and strong, simple gabled massing, the Stratton house is more likely the work of James Corner than William Boone. Its character and detailing are similar to the shingled houses of East Coast architects McKim, Mead & White and Peabody & Stearns, but unlike its eastern contemporaries the Stratton house boasted broad overhangs with heavy stepped rakes that flared upward at the ends. Interior details such as the living room fireplace surround confirm the hand of Corner, drawing on the precedents Corner had illustrated in his book Examples of Domestic Colonial Architecture in New England, published in 1891. With its commanding presence above Lake Washington, intricate design and detailing, and sturdy construction, the Stratton house easily earned the praise of Seattle’s Daily Bulletin, who called it “one of the most attractive in the city.”

Plate 36. “Mantle, Haven House, Portsmouth NH built about 1800.” James M. Corner and E.E. Soderholtz. Examples of Domestic Colonial Architecture in New England. Boston: Boston Architectural Club, 1892.

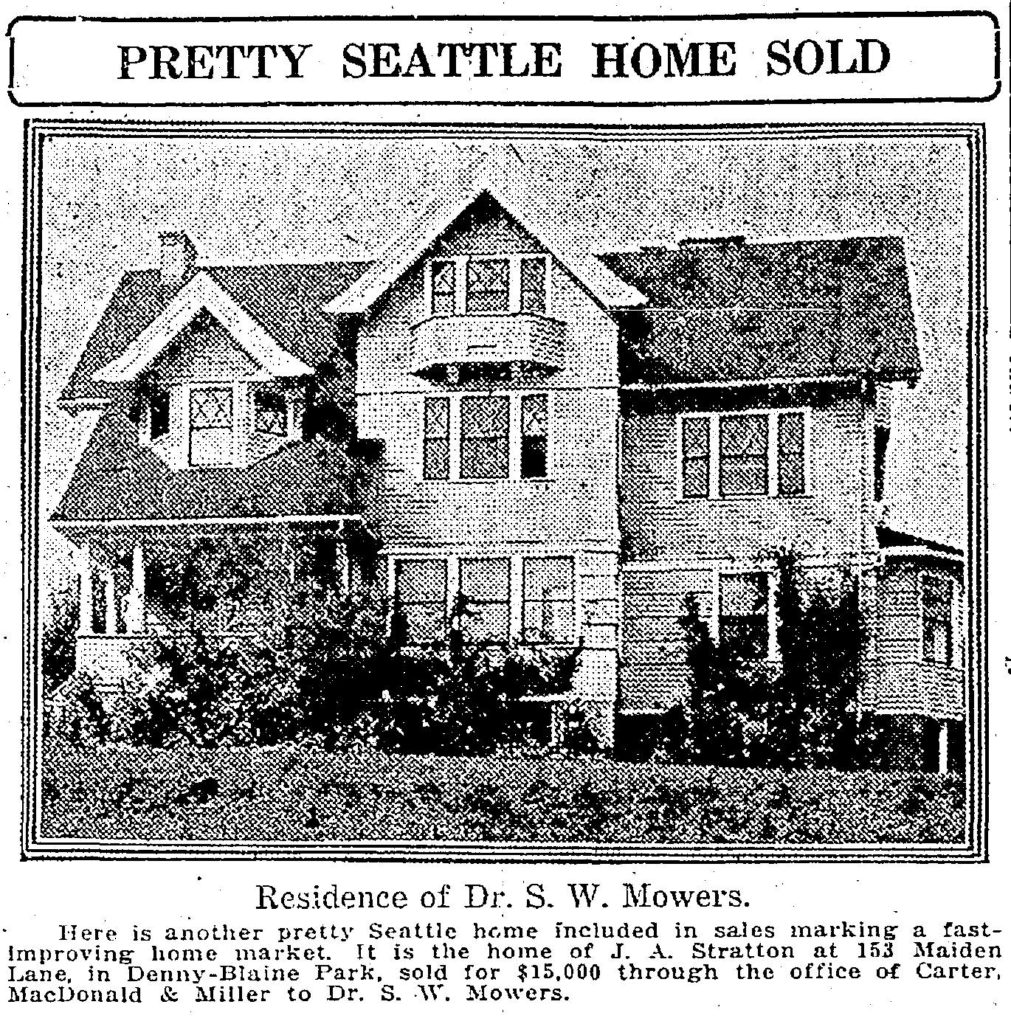

Judge Stratton (1844-1924), his wife Laura and their son Julius – who later became president of MIT and Chairman of the Board of the Ford Foundation – lived in the house until 1920 when it was sold to Dr. SW Mowers, a surgeon, and his wife Maude. At the same time the large property was divided, with parcels sold on either side for new homes. After living in the home for only five years, the Mowers’ sold it to George Dilling, Seattle mayor from 1911-1912, who then sold in 1928 to Edward and Lyle Harrah. Over the next seven years the Harrahs remodeled and added onto the Stratton house under the supervision of architect Alban Shay and later, Sherwood Ford. Trained at the Universities of Washington and Pennsylvania, Shay’s traditional detailing acknowledged and complemented the Colonial work of Corner just years before Shay became a leader in modern residential design while in partnership with Paul Thiry. Sherwood Ford, on the other hand, brought more eclectic styling to the house. Architect of Seattle’s Fox Theatre (1929) and Washington Athletic Club (1938), Ford designed a detached neo-classical carriage house and other additions to the home. They were among the last projects the house would see until renovation and restoration in 2007.

The Seattle Times.